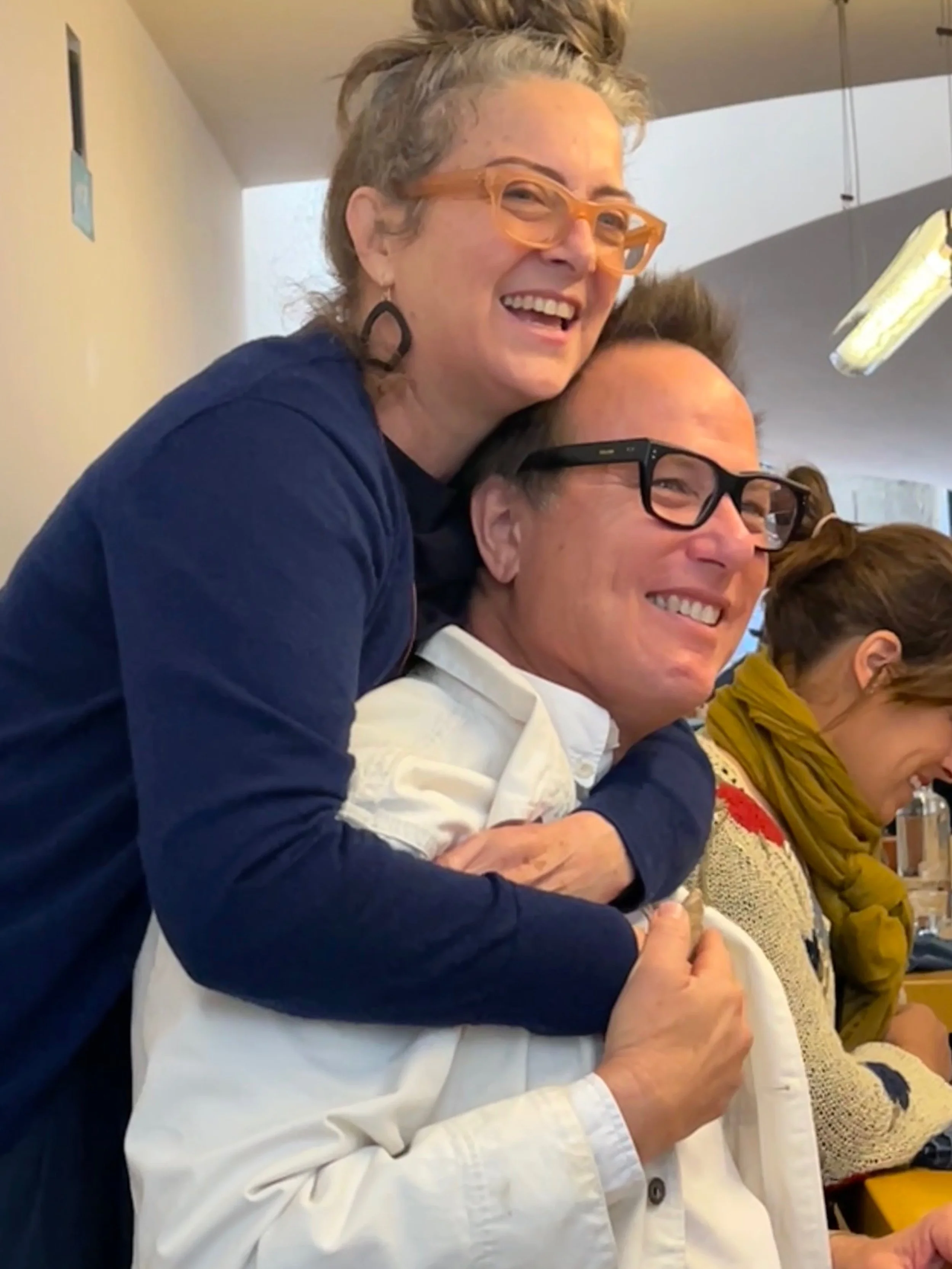

Alice Waters’s Protégés Are Partners in Creativity, as Well as Life

Russ Moore and Allison Hopelain are partners in business, as well as in life. It is in this way that they do everything a little differently. Photos courtesy of Hopelain and Moore.

At Alice Waters’s beloved restaurant, Chez Pannise, Russ Moore landed one of his first restaurant jobs at age 22 with nothing but an apron, spiky hair, and a boatload of determination. Russ had grown up thinking he’d become a doctor, but scrapped the dream when he realized it wasn’t really his dream. So, naturally, it was at one of America’s top restaurants that he built his career from the ground up, being mentored by the greats (including David Tanis, who was head chef at Chez Pannise at the time). But that wasn’t the best part — not even for his career. It was during this chapter in his life that he met the person who would eventually become his partner in business, as well as in life, Allison Hopelain.

When Russ decided to leave Chez Panisse in the early 2000s, he was looking to open a critically-acclaimed restaurant of his own (because, that’s the sort of thing you do if you’ve worked under Alice Waters). Except, he couldn’t do it entirely on his own — he asked Allison if she’d do it with him. After politely declining for about 12 months, she agreed on one condition: their restaurant needed to stand out in a sea of sameness.

So they opened Camino, an Oakland-based restaurant serving Cali-Med-Asian food. Just about everything at Camino felt different from other restaurants. When you came to their restaurant, you’d eat under medieval-looking chandeliers at long wooden communal tables facing a giant fireplace, where all of the food was cooked. The menu changed daily (a slightly crazy business model, they’d admit), but the expectations for each dish were consistently high — when Russ couldn’t find a vinegar he liked enough to cook with, he started making his own barrel-aged bottles. (Today, the couple still sells these bottles; they’re just that good.)

It wasn’t long before Camino had a loyal following, critical acclaim, and a big impact on the Bay Area restaurant scene. But the success wasn’t forever. Perhaps there weren’t enough cooks in the kitchen. Or, maybe the restaurant’s tipless model was just too ahead of its time. But at the end of the day, Camino may have been too impossible of an idea.

Here, Allison and Russ share the ups and downs of running one of the California’s most-loved and unique restaurants for over a decade; what it’s like to be partners in business and life; and what they’ve learned since closing shop.

In 2002, Allison agreed to open Camino Restaurant with Russ on one condition: that it be entirely unlike your average Bay Area restaurant.

You are husband and wife and decided to open a restaurant together in the Bay Area. How did these two things fall into place?

Allison: In the late 1990s, I thought we had the best life and would have been stoked to live out the rest of my days with Russ exactly how they were. But in about 2002, Russ started having ideas about leaving Chez Panisse and starting his own restaurant. He originally had another partner who backed out after the dot com crash. He was looking around for another partner for about a year without luck. We would talk about it a lot at home and I finally said I would do it with him under the condition that it not be like a restaurant — I had a realization at one point after going to a very popular Bay Area restaurant. I remember saying, If that is what a restaurant is, I don’t want one. We looked for a space in San Francisco for 5 years with no luck. We were committed to staying in the Bay Area because Russ’s superpowers lie with the relationships he has with local farmers. A friend suggested Oakland and at first we were reluctant but we found the perfect spot within six months of looking. Rents were cheaper in Oakland and the city felt like it was more underground cool.

Russ: That very popular Bay area restaurant was an industry favorite. It hit every box it was supposed to hit during that era — every dish you were supposed to have in the way you're supposed to have it. But it was completely soulless, and I never wanted to go to those kinds of restaurants. And after that meal, Allison's like, What the f*ck was that? I'm like, Well, that is a restaurant. So that’s what started us off, perhaps on a negative start, but I guess it was an agreement when we started to not just do the obvious, common thing that restaurants do, but really analyze every decision and make it feel personal for every person that dined in. We knew we could do that together.

How do you work and how do you work together?

Allison: At Camino, we had a lot of special events — cookbook and author dinners, weddings, and more. It would be an opportunity to make subtle changes and additions to make the nights extra special. These were my favorite part of having the restaurant, but it was also where we had the most conflict. My dreaming versus Russ’s reality. He would imagine himself physically working through the stations to make the night like I was imagining: the physical labor, the space it would take in the kitchen, how much of his attention it would require. Then we would talk and talk and talk until we came to a version that actually worked and still delivered something extra special.

What are your backgrounds and how did you meet?

Russ: I’m from Redondo Beach, and when I was born in 1963, it was a beachy, suburban, white area. In my late teens and early twenties, I was very punk rock — I came from a gigantic high school and just hated it, so I did everything I could to escape to Hollywood to go see punk bands all the time. My mom was a nurse, and the plan for me was to become a doctor, but as I was getting older, I was more and more disillusioned with where I lived and the environment around me. When I graduated high school, I was a straight-A student, but I was burned-out. One day, my mom suggested I go to culinary school. She was born and raised in Hawaii in a Korean-speaking household, and she cooked in that mixed Hawaiian/Asian style, leaning toward Korean. When she cooked white people food, it was just so bad — my dad liked it, but I would escape these meals and eat noodles in Gardena. Anyway, I thought culinary school was very uncool. It was a time when there was Julia Child on TV and that was about it; there weren’t “cheffy-chefs” during that era. But I didn’t want to go to college, so I went to LA Trade Tech, and I learned how to hold a knife and how to be in the kitchen and soon after that I quit school. I came to San Francisco, and started going into restaurants asking for a job. It was super scary and I was a very shy kid, but the only place that was nice to me at all was Chez Panisse. I got interviewed by one of my favorite people in the world, David Tanis. He was rubbing his eyes with hands, didn’t know what day it was, shuffling papers around, and he gave me the job.

Allison: I’m also from LA, and I took the GED when I was 15, and I then moved to France for a year on an exchange program. When I came back, I went straight to community college when I was 16, and after graduating I got a job working at a stock footage film library. Then I went to San Francisco State for two years. I met Russ through my roommate when he was working at Chez Panisse. He seemed really cool because he had a job at a fancy restaurant and he had a car. We both were dating people at the time, and we were just really good friends. After graduating my boyfriend and I moved back and managed the stock footage library. I ended up working there for 10 years. At some point I had a crisis, and knew I didn't want to be a film librarian. So I quit, and it was at this time when Russ was getting divorced, and something just sort of clicked at that moment for both of us. And then we very quickly got together, and then I moved back up to the Bay Area. We live in the same place today.

At Camino, Russ and his team would cook everything with fire. Photo courtesy of Eater, San Francisco.

Can you describe each other to me?

Russ: Allison’s super smart and direct and stylish and funny, and she has always been stimulating to talk to, even way back. We were friends the whole time I was married, and she was always one of my favorite people. As a work partner, she’s awesome. We had the most idealistic, ridiculous restaurant, and it’s amazing that it lasted as long as it did. But because we backed each other up with our decisions, we made all these rules and we actually followed the rules.

Allison: Russ has a very strong moral code, which is not to say that he is no fun. It’s just that he's very strong willed and has a very strong sense of what's right and what's wrong. And he's super reliable. Something I've never had to worry about, like at work or any other time, is that he will come through. Right now, we’re in this crazy situation in Morocco and things are so stressful sometimes, but I always know that he’s going to do the right thing and that dinner will get on the table, even if everything’s going down in flames, the customer’s not going to know about it, and he’s going to make it happen.

How did you make your restaurant stand out in a sea of sameness?

Allison: When envisioning the restaurant, Russ wanted you to think of it like when you’re driving in the countryside of Italy, and you’re totally lost and it’s dark and you’re starving and you see a stone building with a little rivulet of smoke coming out of the chimney. Would you want to eat there? Hopefully, yes. So, even the design of the restaurant would inform people of what the experience would be like. And we wanted to surprise people a little — not everything could be easily summed up or recognizable at your first dining experience. A restaurant that you “get” after the third or fourth visit. Something that you could continue discovering.

Russ: The kitchen was organized to promote a different approach to cooking. Rather than have a team of prep cooks and line cooks, each line cook prepped the ingredients for the dishes they were making that night. Our idea was that each cook focuses only on one or two dishes throughout the day: prepping it, changing it, tweaking it. I wouldn’t let anyone do stuff they couldn’t do very well, but I would definitely give them stuff they were uncomfortable doing. Cooks worked four days a week, but they worked longer shifts and it ensured everyone was invested in the outcome of their dish. Your dish was all you at the end of the day. It was the greatest job in the world for the right person and the worst job in the world for the wrong person. A lot of people just couldn’t do it this way, they just wanted to be told what to do.

Another thing about our restaurant is that we didn’t want to serve anything we didn’t want to. So, you’re supposed to have certain things at a restaurant, like soup every day. I love soup, but I hate making soup every day, because then you make a soup that’s a sh*tty pureed carrot restaurant soup. For me, on the day I make soup, I’m going to make such a great soup that we’re all going to be excited about it. And then we’re not going to have soup again for a long time. The idea was, Hey, you're coming to our house, and here’s what we have, here’s what we’ve made.

At first, the challenge was selling the concept to customers — a small menu that changed every day, a bar with a tiny menu with spirit brands no one had ever heard of, long communal tables, waiters that rotated positions, and pooled tips.

Why did you decide to make all the food with fire?

Allison: Russ was sort of the fire guy at Chez Panisse. When Chez Panisse would do events around the world that involved cooking over a live fire, Russ would be there. Our original kitchen at home was really small so he would often cook dinner outside in a fire on the ground. We also wanted something that would distinguish the food from Chez Panisse — he had worked there for over 20 years and basically learned to cook there. He decided writing a menu and cooking in a fireplace would add constraints that would spark creativity and send us off into a new direction.

What’s your creative process?

Allison: I like to lie around with nothing to distract me and dream, plot, and map to come up with tiny surprises that are not noticeable except as part of a whole and all in support of the food: the music, the graphics, the glassware, the salt dish, the dress code, the service style, how the table is set, the decorations. We had the idea to make the restaurant feel like a giant feasting hall. We got these big, long, crazy tables where you were sitting next to other diners and it felt really communal. A lot of people would say, Well, you can’t do that. And we'd be like, Oh yeah? The process of building a restaurant was a lot of stuff like that: an idea would come, Russ and I would talk about it all night long, and sometimes we’d make unpopular choices. Some people really did hate the long tables and some people really loved them, just like how our restaurant was great for some cooks and not for others. I don’t want to say it was polarizing, but it definitely was not shooting for something in the middle.

For Russ, he starts with ingredients. He makes his order with no actual dishes in mind, more a feeling of what will work. He talks with the cooks all day long about what ingredients we have to work with. He’s constantly balancing what is available and what we have in the restaurant (literally lists, side by side). He is weighing buying cool ingredients, using things before they go bad, workload, staffing, weather and his whims with creating a balanced menu that will sell evenly.

What are the challenges of working in this business?

Allison: At first the challenge was selling the concept to customers — a small menu that changed every day, a bar with a tiny menu with spirit brands no one had ever heard of, long communal tables, waiters that rotated positions and pooled tips (or eventually we went to no tips). Then it was a staffing challenge — being able to pay people enough to live in the Bay Area.

Was there a moment where you didn't know if your business would make it?

Allison: All the time. Camino was a critical success with tons of long-time, loyal customers but we never made any money. Money was never the real motivator but it got to the point where we couldn’t pay staff enough money to live in the Bay Area. Three things happened within a short period of time that, as I look back, were the beginning of the end. First, we gave a chef a raise and he told us to stop giving him raises because he knew how much money we made (personally and as a business) and there was no way we could ever pay him enough to stay in the Bay Area. Secondly, Russ couldn’t put artichokes on the menu because he was the only person who could clean them without wasting the product. This was a real eye opener for me because I could see how Russ was compromising on the menu due to staffing issues. Lastly, we realized that Camino would have had to become a very expensive and exclusive restaurant to remain in business. All this is to say that we would have had to become a very different restaurant.

What would you have done differently?

Allison: Nothing. Not to say that I didn’t make mistakes but I have no regrets about Camino.

Russ: I don’t know if I could have done it differently, but looking back, I wish I could have set a better example of work-life balance for people entering the restaurant business. I am single-minded enough to be satisfied working hard for no money to make one salad that I feel completely happy with. If we had been in better shape financially, I could have spent more time training cooks instead of working on the line every night.

In Morocco, where Allison and Russ are consulting for a restaurant today.

During the pandemic, you closed your other two restaurants and decided to retire. But today, you’re in Morocco, consulting for a restaurant. Why are you still at it?

Russ: I feel totally satisfied with my career and I don’t need to own another restaurant or work in a professional kitchen again. I’m happy making Camino Vinegar. But I’m open to opportunities where I can put my skills to use and stretch my brain a little. The opportunity came up to create the menu for this restaurant in Morocco, and while I’m so used to just saying “no” to things, this was Morocco — a chance to travel and work in a completely different culture. Plus, it’s a world class surfing destination!

Allison: Russ is always the one to say no, and I’m the kind to imagine what something could be. We can both get frustrated with the other person, because I'm always pushing to do something, and Russ is always pushing not to do something. It is actually a good balance. When this opportunity came along, I thought for sure Russ would say no immediately. But I pushed just a little and he came around pretty quickly. The guy offered to fly us out here to see the project and see what the city is like, no strings attached. So we went, and it was incredible. We could live in this beautiful house, work on a project connected to the arts, and it was an opportunity to live somewhere else part of the year. The work itself is not like having a restaurant — we were hired as consultants, which is not our normal mode — we are more doers than delegators. It’s good for us not to be in charge of every little thing, to collaborate with other people. And honestly, working in a different culture is a great way to question your own culture and learn different ways of doing things.

Russ: Yeah, I’m in their world and learning their systems. But I’m offering a different culinary point of view. “Why am I still at it?” is a good question. I’d be happy, staying at home, surfing and making vinegar but I guess there is the problem solver part of my brain that can still kick in when it needs to. And it does need to — Camino Vinegar is a small operation that can’t really grow much bigger so we need other sources of income. A consulting job like this restaurant in Morocco is perfect because I can help guide the menu in a direction that is really unique in Marrakech, challenge myself in a new culture, and be part of a cool project. The perks are pretty great too–the guy we work for is very cool, very hospitable. We are staying in his beautiful riad and, when he senses that I’m getting stressed out, he gives me his car and sends me to the beach for a surf session. It makes the stress and frustration totally worth it.

Allison and Russ come to the same restaurant every day for the same meal: grilled fish, fries, and bread.

So it sounds like you’re “half retired” in one of the coolest places on Earth. What’s it like?

Allison: Working in a Muslim country is very different than working in the U.S. The motivations, the attachment to outcome, the schedules are different. I’ve never felt so “American” before.

Russ: Right now we’re living in this cool little fishing village, and there’s one restaurant shack that we go to every single day. The chef and owner, Ahmed, shows us what fish he has, suggests one or two for us, and then he grills it outside while smoking a cigarette. And it’s so great.

Allison: Funny thing is that we’ve gone to several different beach towns, and restaurants offering the same meal. It’s grilled fish, salad, bread and french fries. But this guy at this shack actually grills really differently.

Russ: It’s like we found the one. Most people split the fish open and cook it, flat, which is really cool. It’s kind of the way they do it at Contramar in Mexico City. But this guy cooks the fish whole, on the grill, and it's so good and juicy.

As a creative partnership, you both had a great dream and a great success, with lots of challenges throughout the process. Looking back, what do you make of it all?

Allison: Even though Camino closed 6 years ago, there is a community of people who were deeply impacted by the restaurant. I think because there was a strong, clear ethos that ran through every aspect of the place. Recently a former Camino employee passed away so we threw a memorial party for her and it was a chance for a reunion of sorts. People came from all over the country, many that we haven’t seen since closing. Many people made a point of telling us (perhaps a little drunkenly) that Camino was an important, formative part of their lives. That’s definitely what I’m most proud of — what makes it all worth it.

Working with Russ so intensely, and actually creating something (whether it be a restaurant or a cookbook or a community or vinegar), has made for a strong personal relationship. We have been able to develop trust and ways of communicating that has strengthened our romantic relationship. It definitely helped us when we recently remodeled our house — ha! Operating a restaurant is partly a creative endeavor and partly a nuts and bolts grind — kind of like everyday life.