Michael Bierut Reflects on His Storied Career (and He’s Not Done Yet!)

Michael Bierut has made his mark on the design world through his own work and by mentoring future creative leaders . Photo by Yuansi Li.

Michael Bierut started at Pentagram in 1990 with no clients and no team. A lot has changed between then and now — he notably designed the Mastercard logo, Hillary Clinton’s “H” logo for her 2016 presidential campaign, and the building signage for The New York Times. And the breadth of his work encompasses everything from high fashion (Saks) to snacks (Nuts.com) to WalkNYC, the wayfinding system for New York City’s pedestrians.

And yet, 35 years later, he now finds himself in a bookend situation with no clients or team members. This is by design. In late 2024, he conceived a new role where he would now just work with his Pentagram partners as an advisor on select projects and overall business strategy. “The thing that I still like doing and think I’m good at doing, is that I can be in a meeting and unpack something that seems to have contradictions or seems complicated,” he said. “I can understand and translate what a client is saying about their problem into something that is actionable for our team.” If it sounds like a good deal to have Bierut as an executive thought partner, trust your instincts. He works in tandem with his partners, as a left brain to their right brain.

If you’re curious about the guidance Bierut has to offer for work and career matters, but you aren’t one of the 24 Pentagram partners, don’t fret. We recently visited Bierut at Pentagram’s office on Park Avenue South to discuss the keys to leading a team and managing partner relationships, what really matters in a creative career, and what he remains skeptical about after all these years.

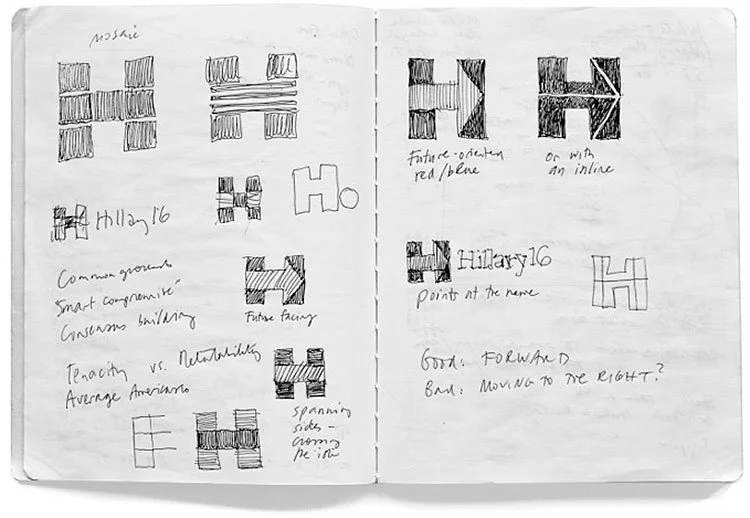

Bierut’s sketches for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign logo (below) and the final version (above). Images c/o Michael Bierut.

You seem like you’re good at pretty much everything. But, more than 50 years into your career, is there anything you still don’t excel at?

I understand P&L statements really well, but I’ll confess I can’t read a balance sheet. I don’t understand what the significance of it is. There are underlying strategic elements of it that somehow elude me.

I tell people Pentagram is a pretty big business run by art school graduates, but we take the financial side of the business seriously. We have a great controller. You’d think that after all these years we’d get a proper managing director in here with an MBA. That hasn’t happened. It has never come close to happening.

What is something you initially thought was important to your career, but then later realized wasn’t?

When I joined Pentagram, I was ambitious and eager, and thought I was poised to make a career leap thanks to this platform. I’m not sure I thought of it in literal terms, but the idea was to get a “seat at the table” in the c-suite. I wanted real authority in terms of design decision-making.

And I found myself getting more calculating, more artificial. I’m not an MBA myself, but I’m married to one, and I’m a quick study who is a fairly good mimic. I can say things that make me sound like I’m smarter than I am. I got good at using a lot of business jargon that clients find reassuring, then I got bored with it because it was essentially hollow. It alienated me from the work that I did best.

Bierut’s Mastercard logo design is smart and elegant.

Bierut’s fingerprints are all over The New York Times building.

How do you feel about the “seat at the table” now?

If you spend time at that table, you find out there is a lot of boring and not particularly interesting stuff happening at it. Also, the people at the table are there for a reason. It’s not because they want one more person who can fit in with the others, right? It’s because you bring something they don’t have. That took me some time to understand.

I can’t pretend that I understand every client’s business strategy on day one or even 100 to the degree that the people in the business know it. But I do understand one part of something that they need to do their business, which is how design might or might not be able to make an impact on whatever those plans are. I keep my hands on that part of the control panel. After I came to this realization, I was happier because I was in my sweet spot and served the overall cause in a more effective way.

It’s sad to see some of the best minds of my generation flip over to the other side and get really interested in cosplaying as business executives. There is this magic thing that we do as designers and honoring that part is worth it.

What else do you remain skeptical about?

I dislike this idea of “educating the client.” I don't think it’s worth spending any time on whatsoever. If the client wanted to learn about design, they could just go to the University of Cincinnati and enroll in the program that I did in 1975. But why would they do that? They brought me because I do that.

Instead, I see client work as an opportunity to educate myself about some new world that I otherwise wouldn’t be granted permission to enter. I’ve been in Page One meetings for The New York Times, at the table with a presidential candidate, and in a lab at a major research university, even though I’m not a journalist, political scientist, or biologist. And that is a reward in and of itself.

Anyone who walks around New York City will see Bierut’s work for the city’s wayfinding system.

If you had to boil effective client relations down to a single sentence, what would it be?

Talk less and listen more.

What are one or two lessons you’ve learned about effectively leading a team?

When I started at Pentagram, I was 33 and my designers might be five years younger than me. Now I’m 67 and the designers I’ve been working with weren’t even born when I started at Pentagram. I’m no longer a big brother, and I’m not even a father figure — I’m a grandfather.

As I’ve gone along, I discovered that it was more interesting to hire people for my team who weren’t replicates of me. When I worked for Massimo Vignelli, I think he saw in me someone who could faithfully execute his style. And I began hiring like that at Pentgram initially. But then I got bored with it and started hiring people who had different backgrounds, skills, and a point of view than me. Hiring for that tension was actually more productive than hiring someone who could do this seamless output based on my vision.

Another core philosophy of mine is to make sure every person working with me has the biggest view of the client project picture that I could give them or that they could take on. Because if a manager just says “execute this system,” it’s just work to the employee. But if you tell your team the big idea you are going for and put them in the deep end, that benefits them as designers and thinkers and makes their thinking more interesting and productive in the long run.

If you had to pick one project as your greatest hit, what would it be?

With me, it would probably be something to do with designing Hillary Clinton’s logo for her 2016 presidential campaign. If I live long enough, that might seem like ancient history, so who knows whether that will be remembered.

This distinctive packacking is just fun.

To take on your new role, you had to convince your partners to support the move. And you mentioned that made you feel anxious. Why?

At Pentagram we have this shared belief that there is nothing more wonderful than showing up every day and designing something. What if I’m not designing anymore? I felt self-conscious about breaking away from the faith and diminishing what everyone else was doing. It’s not like I had these overwhelming creative impulses that have been suppressed and now would burst forth. It was this genuine curiosity about what would happen if everything was different.

How have things gone so far?

I have to admit it’s been a little confusing for me. I like to run every morning. I do it compulsively, and I have a paper calendar where I make my Xs each day I run. It is this same compulsion that drives me to show up every Monday, so I had the underlying fear of, What would happen if I just stop doing it? So the biggest challenge is working not out of routine, but as a conscious choice I have to consider every day.

You mentioned how your younger team members and partners can design a way that you don’t today — in more dimensions and with more focus on digital and motion graphics. What do you make of it? And how does it feel when a different generation has certain skills you don’t?

Of course it’s intimidating, but it’s also thrilling. For me, watching younger designers find their footing in this new environment is like seeing a new musician take a classic song to some incredible new place. That’s the way the world moves forward.

A question people might then want to ask for their own learning is, How do I stay relevant when the skills I have mastered are no longer the perfect fit for the time period and business climate? What are your thoughts?

I can’t speak for everyone, but I’ve found it’s useful to think in terms of the different roles we can assume over the course of a long life. We go from being performers to directors, from proteges to mentors. It’s about understanding where you are in the arc of your own story.

If you had to give yourself a grade for your work over your career, how would you grade yourself?

A solid B+. I wasn’t even the best designer in my class in college, and there are people who are better pure, intuitive designers. But doing this work has permitted me to mentor a lot of younger designers, have a fantastic collection of partners, and work with clients I’ve learned from.

You’re modest. I would have given you an A.

There is a lot of grade inflation going on these days, but, yeah.