Jameson Proctor: Taking Risks Is Vital to Standing Out

Jameson Proctor shares his career twists . Images c/o Proctor

Jameson Proctor cites his maternal grandparents–plus a Les Paul guitar–as inspiration for his career that has evolved from executive chef to the Executive Digital Director, Partner at Athletics. His grandmother nurtured his creative side, teaching him to cook, from fried chicken to a roux to the simple pleasure of a sweet peach splashed with cream. Meanwhile, his granddaddy was an electrical engineer, a trade he learned in the Navy. From an early age, Proctor borrowed his granddaddy’s Apple II+ and developed a passion for technology writing games and graphic demos.

As for the Les Paul guitar replica? That contributed to Proctor being “not so great at college.” After spending most of his time playing in bands, writing highly-derivative poetry and cooking in a diner, he made it one semester shy of an English degree. So Proctor returned to his hometown of Atlanta and cooked at local institutions before becoming the Chef de Cuisine at the W Hotel. His restaurant career provided him enough standing to move to New York City and land a job working in the kitchen for Top Chef’s Tom Colicchio’s (now closed, yet missed) sandwich shop, ‘wichcraft. After another career pivot or two, Proctor made his way from the kitchen to the creative studio Athletics, where he and his team work with a range of clients, from the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Museum of the City of New York, and The New York Review of Books, to their latest projects for IBM Consulting and the healthcare company Galileo.

Because creative careers are a series of twists, evolutions, and pivots that can turn out to make sense in the long run, we pick up Proctor’s story at ‘wichcraft in New York City where he weaved his maker spirit and tech prowess into a completely new role that led him to where he is today. Over an icy Americano cocktail–one part Vermouth, one part bitters (usually Campari) and one part soda–Proctor shared how he advanced his career from chef to Executive Digital Director, why taking risks is vital to creating anything meaningful, and the importance of being able to translate your experiences no matter which direction your career takes.

We pick up when you’re working in the kitchen at ‘wichcraft. How did you make the jump from chef to ‘wichcraft’s Director of Technology?

During my career as a chef, I was always the guy that the front of house would come to when something digital needed some love–the site needed to be updated with the day’s special or the point-of- sale system wasn’t working. I’d be making a sauce and they’d always find me: ‘Jameson, so and so isn’t here today, can you help us?’

As I worked for Tom, I started to visualize this future where, perhaps, I could synthesize my experience in the culinary world with my ongoing interest in computers and digital. I’d been working in kitchens since I was 16 and, while there are things I love about it, it’s a grind. At the time, Tom was working with folks on a new online ordering system, and I inserted myself into the product design. I had no idea what product design was at the time, but I knew what a restaurant operator needed from an ordering system.

Inside The New York Review of Books redesign

You’ve got Tom, a culinary icon, on one side and product designers on the other. Where and how exactly did you insert yourself between these experts?

I suggested that we experiment with the Google Maps API. We were managing deliveries manually before they started developing the system. We'd been taking orders over the phone, and had to look up addresses to see if they were actually in the delivery zone. It made no sense to do it manually. On nights and weekends, when I wasn’t managing the ‘wichcraft kitchen, I worked on how we could bring this API to the customer experience and make the ordering system digital.

It started to become apparent that I had value to this growing organization beyond managing the kitchen. That led me to take on a new role in the company and become the Director of Technology. Using a crude AI machine learning system, we built something that could predict what any of the 16 ‘wichcraft units across the city needed to order at any time, taking into account factors like weather and holidays. I learned we could build something that’s lean and takes an MVP (minimum viable product) approach and have something that does just what you need it to do. That thinking has continued in my career and has become more important than ever these days.

Why has that thinking become more important than ever?

Because, in the digital world, the rate of change has significantly accelerated over the past several years—with real exponential growth resulting from the pandemic when any remaining holdouts had no choice but to embrace digital. Lean thinking and getting MVPs out into the world allows our clients to interact with concepts earlier and opens that critical feedback loop with the audience up sooner. It gets you out of the echo chamber and into the real world. It removes abstraction and allows people to experience creative and strategic thinking. That's what ultimately drives products and experiences forward in my humble opinion.

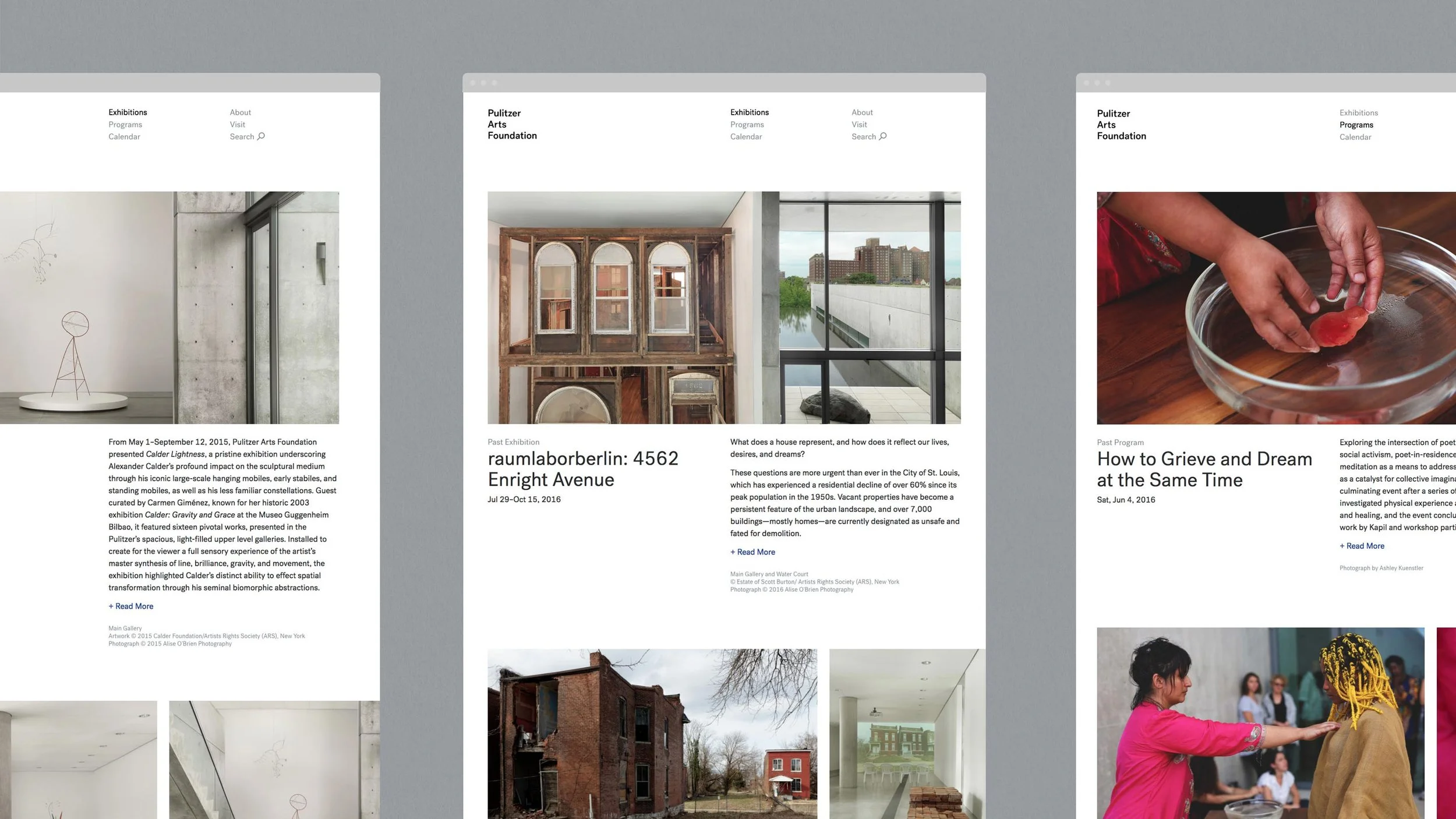

A view of Athletics’ work for the Pulitzer Arts Foundation

What did you learn from Tom about creativity?

Coming out of the ‘90s and the early 2000s, there was a very different management culture. It was dictatorial, hierarchical, very much ‘do it my way or don't do it.’ But Tom responded thoughtfully in a way that clearly demonstrated that he was listening to your ideas. He didn't always agree, but, if he disagreed, he articulately expressed his case. Where I think that ends up, especially when we talk about the creative life, is the idea of leading with acceptance, positivity, and being an active listener. That gives creativity the room it needs in a conversation and collaboration to come to fruition.

Another is the idea of working with constraints. When I look at the modern creative studio, this isn't a new idea, but it's a true idea. Creativity is the last thing that we have that differentiates us from others. It's our superpower. But it's a resource and like any resource, it has limitations. So how do ensure that the ideas that come out of it make the best use of that resource? Controlled pressure can lead to creative thinking.

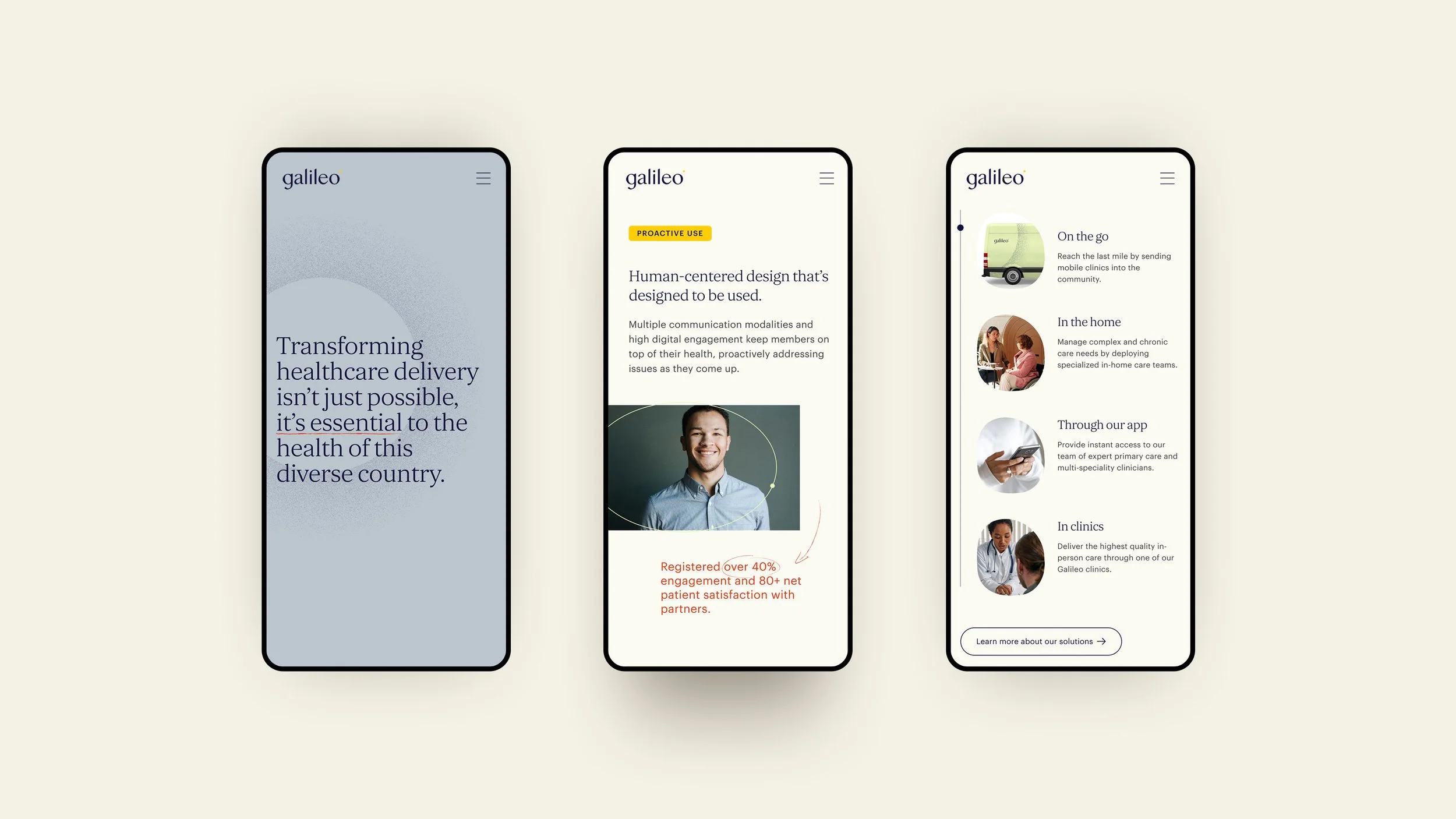

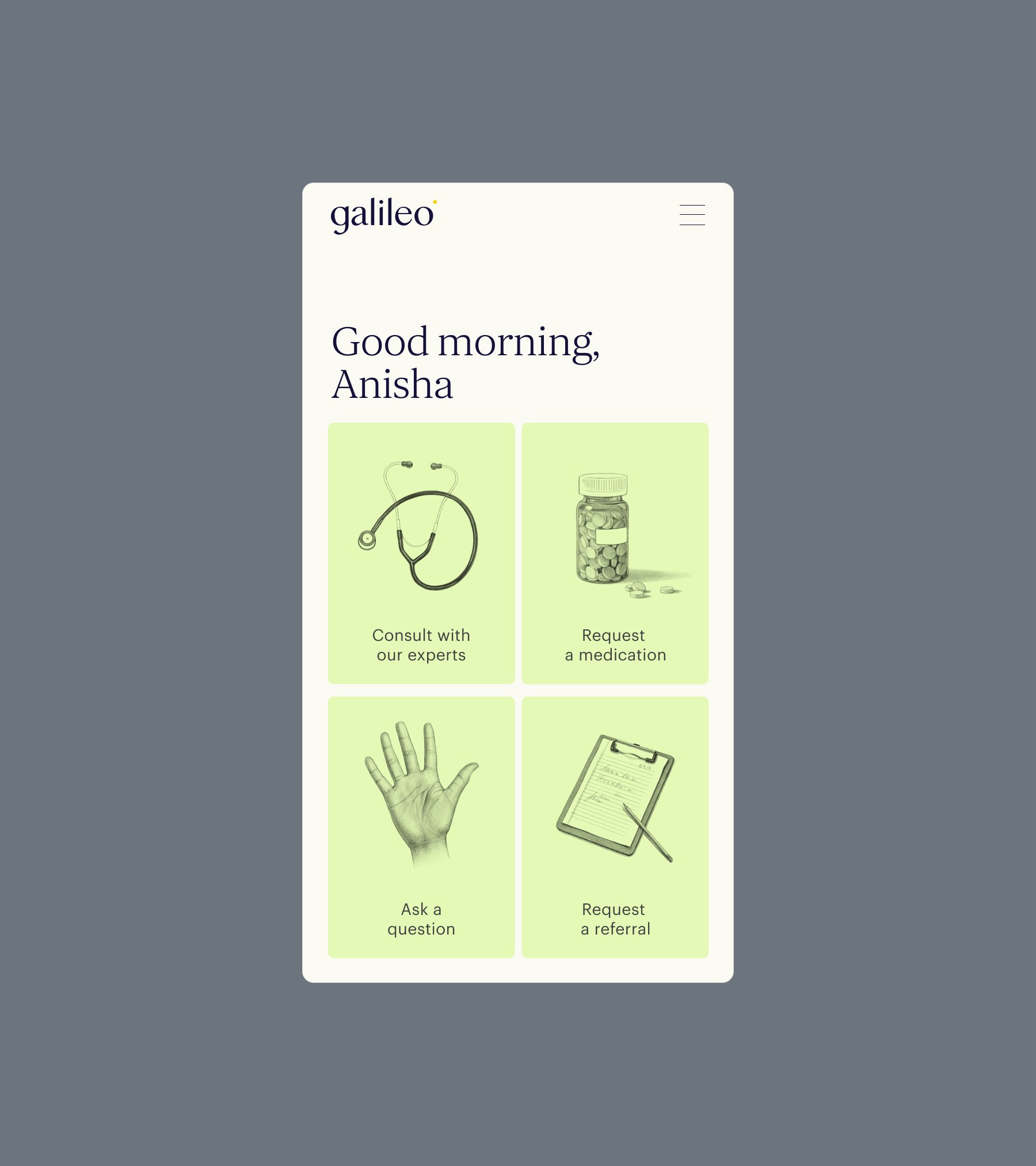

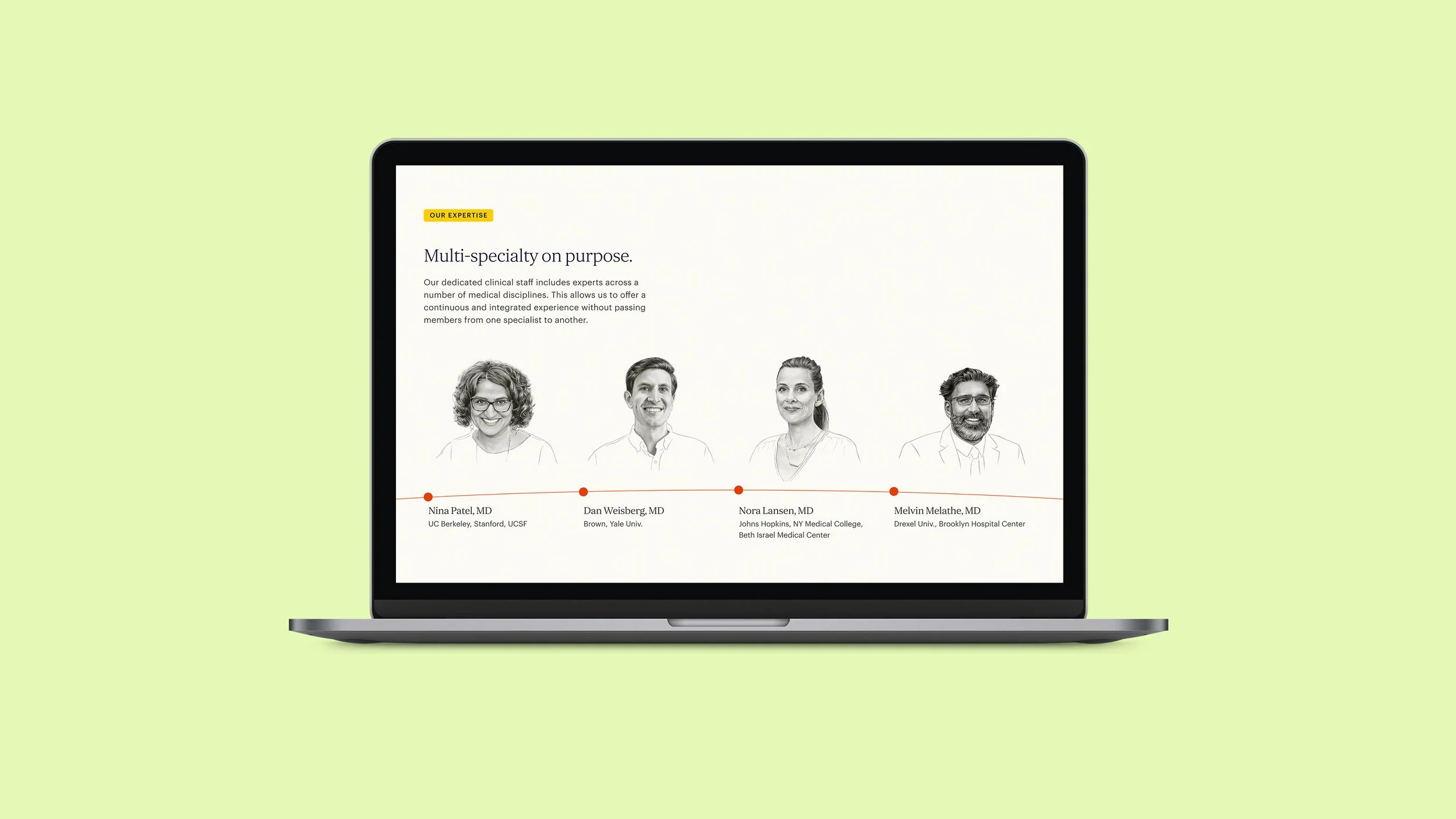

Athletics’ work for Galileo humanizes healthcare and technology.

Now at Athletics, what’s it like to work with more institutions like the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, the Museum of the City of New York, and the New York Review of Books?

Like a lot of New Yorkers, I have a love-hate relationship with the city. I always talk about its ugly beauty. But there's something about it that really resonates with me. That goes back to working with Tom. From ‘wichcraft in Bryant Park to being in the back hallways of Rockefeller Center to the basement of the New York Public Library, that trajectory is part of developing a love for the city.

How do you create experiences for beloved institutions?

It’s all about keeping yourself open and being an active listener. I try to share authorship with my team and our client teams. I know collaboration is such a buzzword that gets thrown around so much that it loses some of its meaning. A few embrace it for what it is as defined. Then you establish a space of trust and mutual respect and that becomes the foundation of good work.

What’s fun about working with institutions is you have such a heritage where you get to dive deep and maybe bring things back to the surface that are relevant and topical today. You're listening to the history and then you come back with a thoughtful take on how that heritage can inform the brand and experience that you're trying to create.

Heritage brand clients can be hesitant to change when they are a successful known quantity. How do you get them to come along with you as you lead them into a new version of themselves?

The New York Review of Books is a great example. They've been a client of Athletics’ since 2013. Throughout the course of that relationship, we were always trying to move them to a full redesign of the publication in digital. They were always hesitant to make that change.

They tasked us with attracting a younger, more diverse audience and to keep the loyal audience that had been subscribers for decades. We did a deep dive across the cover art for 50 plus years and identified trends around palette typography, and illustration. Then we came back to them with a system that was brighter, more colorful, and graphically bold.

The end result looks great. How do you frame those conversations when you’re asking clients to trust you based more on gut feel and experience than data points because you don’t necessarily have them?

In the world of commercial design, creativity is the one real differentiator. Conversations around validation data and metrics are important, but there is something about that creative spark that's immeasurable. If you try to quantify that you run the risk of extinguishing it. If there is not some risk being taken, the odds that you're doing something that is truly distinguishing are quite low.

Whenever you came to a pivot point in your career, what framework or questions helped guide you to take the next step?

Each time that I came to an inflection point, it was time for creative visualization. I’d say to myself: This is where I am. Where am I going? And what do those next steps look like?

If you could go back and give your younger self advice on your career evolution, what would you say?

Something that has been valuable throughout my career is the ability to articulate translatable experiences. It was valuable in pivoting from being a cook to a chef to a Director of Operations to a Director of Technology to moving out of the culinary world altogether.

Today it's useful in moving into an industry vertical where we don't have direct experience. I can have that conversation with potential clients and let them know that, even if we don’t have anything in the portfolio that speaks to exactly what you do, I can explain how work we’ve done translates to their experience. That also applies to giving direction to the team and clients. Even if we haven’t faced a particular challenge and we’ve never come up with that specific creative solution, we have done things that translate.

This takes us to your most recent project with Galileo. You have experience in the culinary, publishing, cultural, and arts worlds. How did you translate those work experiences, plus the skills you’ve developed throughout your career, to the world of healthcare?

I'd say it's less about being able to translate my experience to healthcare per se and more about leveraging my varied background to quickly develop a breadth and depth of understanding of a client in an industry such as healthcare. That background helps me to better and more quickly understand opportunities and challenges and work towards creative and strategic solutions. If I had to put my finger on it, I'd say it's a certain degree of risk tolerance or, maybe more positively, openness. I've been open to new ideas and experiences throughout my adult life. It's what led me through the worlds of music and cooking and digital design and more. It's what helps me understand our clients and work with them and our team to think creatively about how best to help them.

If you’d like to read more from The Creative Factor, sign up for our newsletter.

Plus, check out the following pieces: