Sara Little Turnbull: A Creative Force Behind the Design of the N95

/ JUNE 05, 2020

Sara Little Turnbull was trained as a designer, though she considered herself a cultural anthropologist. For instance, when one company asked her to build a burglar-proof lock, she visited prisons to research how convicted felons did it. Sara passed away in 2015 at age 97, but not before designing a wide variety of household staples and developing a reputation for tackling problems in unique ways.

Hers is an underdog success story, from growing up poor in Brooklyn to becoming a trusted behind-the-scenes advisor to executives at Coca-Cola, Revlon, Pfizer, Nissan, and more. Many of Sara’s corporate clients stayed with her for long stretches; 15 years was considered a “short-term” client. Why did they all trust her? “Sara connected very well with the most senior executives in understanding their issues and what they needed to do to move the company forward,” says Paula Rees, principal of Foreseer, a Seattle-based design firm and a board member of the Sara Little Turnbull Center for Design Institute. Another important factor? “She made them billions of dollars,” says Rees.

Product design might have been a bit more glamorous back in Sara’s day. Photo courtesy of the Sara Little Turnbull Center for Design Institute.

Standing 4’11”, Sara was often referred to as “Little Sara” as a child, so ran with it and changed her maiden last name from “Finkelstein” to “Little.” At her first job at a New York City ad agency, Sara shared an office with her boss, the art director. According to the video interview, A Life by Design, when Sara asked the art director why she was chosen for the job, the art director replied, “You were the right size.”

If We Could All keep in Mind the How’s, Whys, and Wherefores

Following a nearly 20-year run as the Decorating Editor at House Beautiful, Sara struck out on her own and started Sara Little Design Consultant. By then, she already thought about design far beyond aesthetics alone. In 1958, Sara published an ahead-of-its-time essay in Housewares Review titled, “Forgetting the little woman?” It zeroed in on user-centered design long before it became mainstream. “She would chuckle at the term ‘human-centric’” says Rees. “What else is it, unless you’re designing for pets?”

Sara’s thesis declared that manufacturers kept creating products for distributors. The manufacturers listened to what the distributors thought they needed to sell to consumers, rather than learn from customers directly. Companies obsessed over how products looked, whereas Sara argued that the type of questions they should be answering about their products were more functional: How does it perform? How much does it weigh? How does it feel in the hand?

Sara considered a 15-year client engagement to be “short-term.” Photo courtesy of the Sara Little Turnbull Center for Design Institute.

The men who made products for women didn’t have a clue as to what the female customer really wanted, so Sara provided “user behavior” context. “The majority of women have a series of jobs to do,” she wrote. “Keeping the husband alive; keeping the kids out of jail; preventing pests from taking over the house…and, of course, looking lovely and serene when the 5:32 pulls in at the station.”

Sara closed her essay on a more serious note: “If we could all keep in mind the how’s, whys, and wherefores of her living habits, manufacturing and selling would not have to be done with a crystal ball but could be done with reality itself.”

Don’t Just Look, See

When we view the world around us, Sara said we should not just look, but see. Her intense curiosity led her to read five newspapers a day, though not necessarily for the day-to-day particulars. “I wasn’t reading the news, I was reading about change,” she says in A Life by Design. By looking at the world from this perspective, Sara developed fresh ways to see the everyday, then connected unlikely dots to make order out of the chaos.

If you went to Sara for a creative spark, she might have directed you to her research files, neatly organized around 375 sub-topics. “She might pull out a file that had nothing to do with anything you were thinking about, and you would have an aha moment,” says Larry Eisenbach, founder of Deadline Design Consultancy and board president of the Sara Little Turnbull Center for Design Institute. Her breakthroughs resulted from going out in the world and talking to people, linking unlikely ideas together, and applying human intuition. “There is serendipity in the creative process,” says Eisenbach. “It's not a linear thing.”

The “Forgetting the little woman” essay brought Sara attention from global CEOs; General Mills, 3M, and Corning became three of her first clients. At 3M, Sara began in the Gift Wrap & Fabric division, where she developed America’s first pre-made “magic” packaging bows. Then she began experimenting with 3M’s non-woven textile technology and dreamed up 100 new product ideas that she presented to 3M executives in 1958. The presentation was titled Why?—Sara’s go-to question. According to Design Museum Online, she told the executives, “This is not merely being in the ‘textile business.’ This material is a research and development innovation that will bring profits in new markets to 3M.”

Never one to sit still, Sara was also the founder and director of the Process of Change at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, which she led for 18 years. Photo courtesy of the Sara Little Turnbull Center for Design Institute.

Sara’s presentation caught the eye of the 3M scientist who invented the non-woven textile material but hadn’t figured out enough ways to sell it. He was impressed with Sara’s creative initiatives and assigned her the task of designing a molded bra cup. As Sara experimented with the bra cup, she happened upon another potential use—a medical face mask. She had spent a considerable amount of time in the hospital during the mid-1950s, with the death of her sister, then father, and mother. The hospital experience showed her the need for a face mask that could filter particles and sit comfortably over the face and mouth with a stretchy band to avoid tying.

Creativity as a Tool for Change

According to Fast Company’s history of the N95 respirator, the design of the medical face mask evolved over 500 years, beginning with the bird beak-shaped masks people wore in the 1600s to combat the plague. Those aimed to protect wearers from the plague’s smells. (“People thought that by protecting themselves from the smell of the plague, they’d be protected from the plague itself,” wrote author Mark Wilson.) In the 1900s, medical face mask designs were all over the place—some described as a “glorified handkerchief” while others “hoods with masks, like diving masks”.

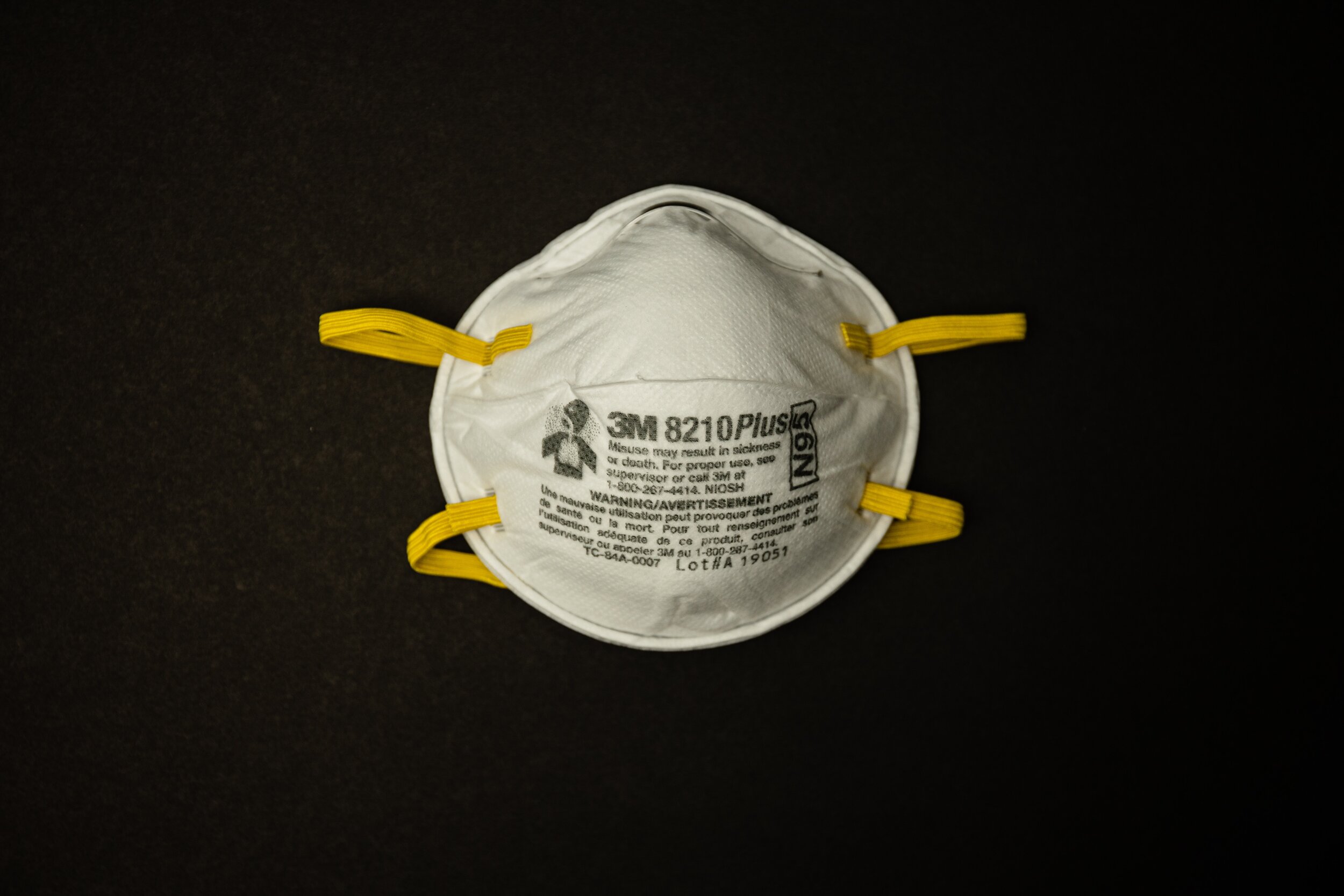

In 1961, Sara designed the bubble shape version we’re familiar with today. Count the bra cup as inspiration. “She figured out that she could take this bra cup, turn it around, and make it be the mask,” says Rees. The only thing it couldn’t do was filter pathogens. It wasn’t for lack of trying. “They went through a decade trying to figure out how they could get it to be a medical tool,” says Rees. “Sara’s first intent was a medical mask.” Still, Sara’s bubble mask design certainly influenced the first single-use N95 “dust” respirator that was developed by 3M and approved in 1972.

Incidentally, 3M never moved the bra cup out of the prototype phase. However, Sara may have developed another business idea for the non-woven textile technology during her research. Sara, who called herself the “advertising business’ Jewish mother,” once stuck the bra cup in a bowl of chicken soup just to see what would happen. The material absorbed the fat. “3M is a major supplier of non-woven oil spill booms, these big rolls of material that suck up oil,” says Eisenbach. “We can conjecture that that material came out of Sara showing them this material was good at doing this.”

Sara’s design accomplishments were broad and ranged from the design of interiors, furniture, appliances, car interiors, cosmetics, personal care products, paper products, house goods and cleaning supplies, dining and cookware, to new foodstuffs and space suits. Specific products included the first pre-made bows for 3M; Bugles snacks, Bacos, and cake mixes for General Mills; CorningWare, Corelle, and the glass cooktop for Corning, to name only a few.

Rees and Eisenbach agree that if Sara were here today, she’d jump into this moment of change and transformation. “She said designers are those who acknowledge change and use their creativity as a tool for improving their times,” says Eisenbach. “If there isn't a better thing to say that we need right now, that's it. Creativity is a tool for improving these times.”

The next time you’re in Seattle, you can visit the Sara Little Turnbull Center for Design Institute.

Photo courtesy of the Sara Little Turnbull Center for Design Institute.

Cover photo by Jonathan J. Castellon on Unsplash

Matt McCue is the co-founder of Creative Factor. He lives in New York City, but is willing to travel long distances for a good meal.