Designing for Lions, Tigers, and Bears (Oh My!)

A lion enclosure at a zoo in Moscow. RIA Nowosti / Mikhail Fornichev. Design by Amanda Tuft.

Thanks to zoo closures during the pandemic, many zoo animals have lived their best lives. The most fortunate ones were let out of their enclosures to wander around properties and even mingle with other species, sans human visitors. But, as we inch to the other side of the pandemic and zoos reopen and animals go back their captive lives, maybe it’s time we stop and consider the trade-offs of zoo design?

Everything we create—and even enjoy immensely—is full of inevitable trade-offs, including the design of zoos. They are made by humans, for humans, and the architecture plays with emotions. “Zoo design is one big illusion,” says German architect Natascha Meuser who has literally written the book on the subject.

Zoos are also big business. According to the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, more than 700 million people visit zoos and aquariums each year. The San Diego Zoo, along with its new Zoo Safari Park, saw a combined record attendance of 5.5 million visitors in 2018.

Here, Meuser shares how designers have weighed the trade-offs of zoo design throughout history, why we, as society, like to make unpleasant things look pleasant, and what we can learn from zoo design and apply to our own pursuits (it involves sleeping crocodiles).

“In the field of experience design, there is often discussion of things that make our lives easier. But there is less talk about design that is physically or emotionally harmful. Why?”

A view through the armored glass of the hippo pool at the Wroclaw Zoo (photo: Leszek Solski).

When you wrote your book, you initially thought zoo design would be a straightforward architecture issue. But it became about much more. What did you notice?

Today, we must understand that society’s view of the optimal co-existence of humans and animals has altered fundamentally since the first scientifically-managed zoological garden was built in Paris in 1793. This change in human conceptions of the wild animal, from a mere showpiece to a being with rights, is now more than ever a topical issue.

People can try their best with conservation efforts and more open enclosures, but zoo animals are still locked up. How have designers viewed this trade-off throughout history?

With an impressive ignorance towards the needs and rights of animals! But in the past, we just didn’t know better. The architectural history of zoos is a reflection of Western humanity’s relationship with animals: Christian values, academic emancipation, and political power are key factors. Developments always crystallized in the form of buildings and architectural reform. As with general notions of appealing architecture, humanity’s relationship with architecture and animals also changed. The zoo evolved from a collection of living trophies and a museum with live exhibits to an amusement park with a moral duty.

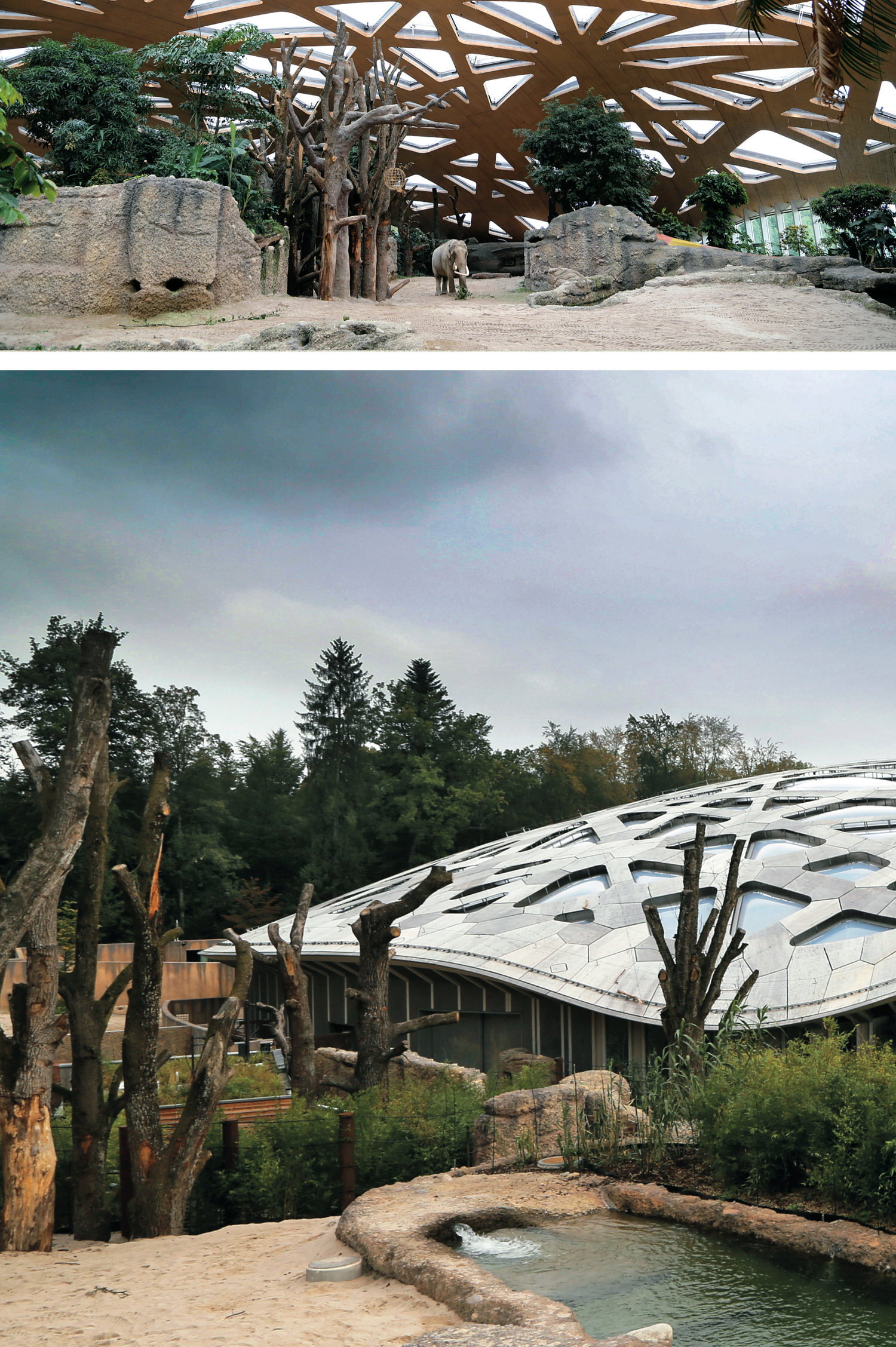

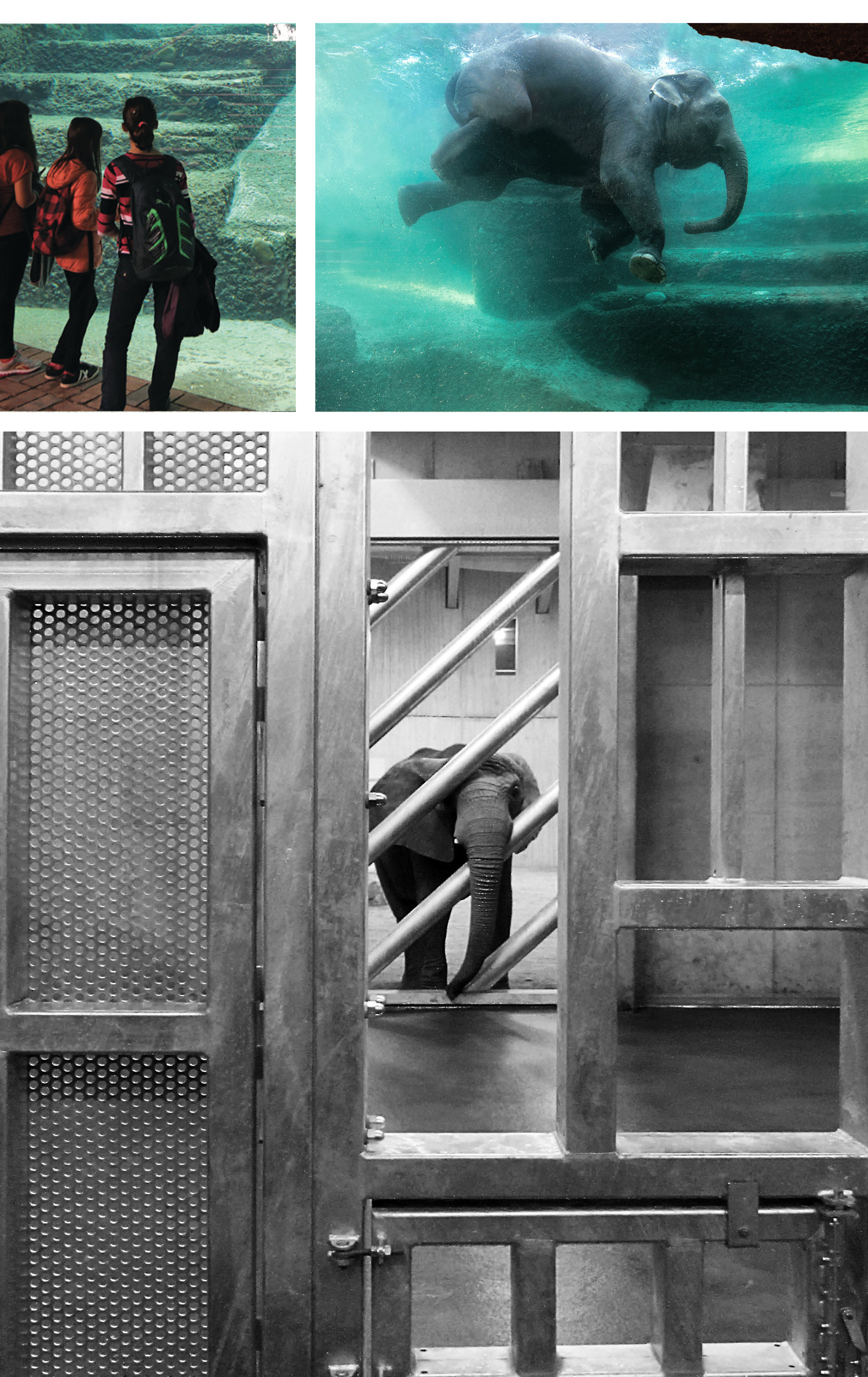

From top: The outside of the Asian Elephant House at the Zurich Zoo (photo Natascha Meuser); the Asian Elephant House pool, which allows the elephants to drink up to 100 liters of water daily (photos Natascha Meuser and Jean-Luc Grossmann); whereas the elephant enclosure at the Zurich Zoo boasts a beautiful, modern design with lofty indoor spaces and outdoor areas to roam, treatment rooms behind the scenes are a stark reminder of the business of being a zoo (photo MKK Architects, Schwerin).

What role has human psychology and emotion played?

Atmosphere is part of any spatial situation. And architecture in zoos is playing with emotions. Almost all the perceptible properties of architecture and landscape architecture are experienced primarily through the atmospheres they create.

It is not only the building, with its spatial forms, but also the atmosphere of a situation that needs to be as harmonious as possible. The staged nature of a zoo has an atmospheric identity that can be derived from the characteristic atmospheres of the areas of origin of the respective animal species.

A major turning point in zoo design occurred in the early 1900s when German animal trainer Carl Hagenbeck introduced the cageless animal enclosure. Tell us about what he did and its impact.

In his panorama zoo, Hagenbeck showed, for the first time, an impulse that allowed zoos-to-date to shed their ‘cute pavilion’ look, liberating them and turning them into independent architectural landscapes. The animals were no longer cordoned off from the viewers. They were now visually transported from their cages and presented on a natural stage.

The fact that Hagenbeck had this idea may have something to do with his origins. In addition to his activity in the animal trade, he was well aware of the physical capabilities of animals and knew how large trenches had to be built from his practical experience in the circus. Hagenbeck’s aim was to give the viewer the feeling of seeing animals in their natural surroundings; he didn’t design enclosures only to perform a function. The idea was to reflect the image of the natural environment of each species.

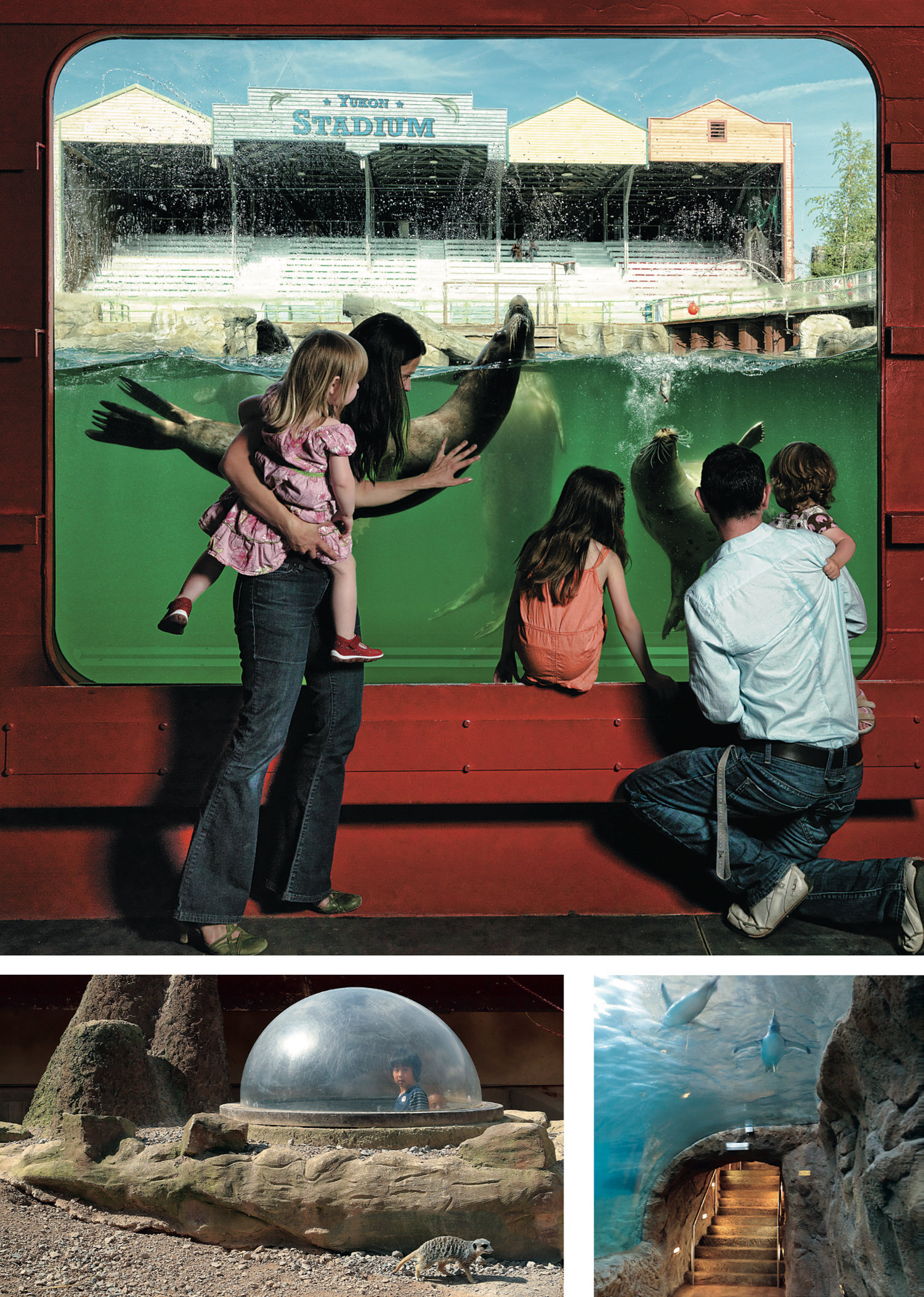

Top: Theme World Yukon Bay in the Hanover Zoo, 2010 (photo: Dan Pearlman Markenarchitektur / Frank Roesner); Getting a meerkat point of view at the London Zoo (photo: Natascha Meuser); Bottoms-up in the penguin basin of the Wuppertal Zoo (photo: Natascha Meuser).

What did you learn about zoo experience design that you would like to see applied to other areas of business?

Creating immersive environments is a very modern way of storytelling. Although this is still mainly analogue, zoos are already starting to introduce 3-D projections. For instance, if a crocodile is asleep, visitors can watch it moving on projections: 3-D media is starting to conquer the zoo world.

Why do you think we, as a society, try to make unpleasant things look more pleasant?

We were all looking for a paradisiacal state. When we go to the zoo, we want to see an intact world. This longing is deeply rooted in us human beings.

In the field of experience design, there is often discussion of things that make our lives easier, such as a delivery app. But there is less talk about design that is physically or emotionally harmful, even though it’s more prevalent than we like to admit. Why?

Perhaps, it is because we don’t find it easy to address issues that are not easy to change or face difficult truths. And from our contemporary viewpoint, there is much that can still be improved on in zoo design.

If you’d like to read more from The Creative Factor—such as Morten Bonde’s story about working as a LEGO Art Director while losing his sight or how Alinea’s designer has reimagined the coffee maker—subscribe to our newsletter.